by Danielle Pasquel

The direct link between socioeconomic status and human health has been well established in the field of public health. Poor communities face an array of distinct economic and social challenges that have quantifiably adverse effects on overall health and health outcomes. Many interrelated factors dictate the relationship between income and health, including sociopolitical status, access to and quality of healthcare, health literacy, nutritional awareness, stress management, and exposure to environmental hazards.

Health disparities in New York City (NYC) provide a perfect example. The Bronx, particularly the South Bronx, is the poorest congressional district in the country, and has some of the worse health outcomes in the nation—it isn’t difficult to see the connection. There is an overrepresentation of racial minorities in poorer communities—African Americans and Hispanics account for 43% and 54% of the South Bronx population, respectively (U.S. Census 2013). The community suffers from a host of health issues, including disproportionately high incidences of obesity, diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease, mental illness, and other chronic health conditions. Moreover, individuals from the Bronx are more likely to experience higher morbidity and mortality compared to white counterparts from middle-income or wealthier neighborhoods afflicted with the same disease, which is also the case nationwide.

Many urban health and epidemiological studies have documented the effects of environmental factors on the health of community residents, such as proximity to hazardous waste sites, quality of air and water, availability of high quality food, and access to open green spaces. Historically, the burden of NYC’s environmental hazards have been disproportionately imposed on Bronx communities, through biased land usage policies instituted by the local government and corporate interests. For example, the South Bronx currently contains nine waste transfer stations, almost one-third of the total number in NYC, but only 6.5% of the City’s population. This large density of waste facilities, particularly on the Hunts Point peninsula, imposes a heavy environmental burden on the surrounding neighborhoods. In addition, there are other industrial and polluting land uses, including the Hunts Point Cooperative Market wholesale food distribution center (the largest in the world), power plants, and extremely heavy industrial truck traffic, that all exacerbate the environmental encumbrance experienced by Bronx residents.

A Brief History of the Environmental Justice Movement

Environmental justice (EJ) is defined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies” (1995). Modern day EJ issues have existed arguably since the advent of the Industrial Revolution, characterized by a series of technological advancements and concomitant transformations of social life. The large-scale production of commercial goods required the siting of manufacturing facilities, which also produced an immense amount of solid waste and air pollution. The factories tended to be located in poorer areas of cities, where construction and overhead costs were lower, cheap labor was plentiful, and complaints about environmental toxicity were easier to ignore. This is how environmental injustice develops: communities lacking wealth and sociopolitical representation are forced to bear a disproportionate amount of the environmental burdens deriving from the industrial processes that benefit everyone else.

The study of EJ and the accompanying social movements only reached widespread recognition and momentum in the early 80’s. In 1982 the residents of a poor African-American community protested against the siting of a toxic waste disposal site in their community in Warren County, North Carolina. This is often recognized as the birth of the EJ movement because it was the first issue of its kind—an environmental justice movement initiated by a low-income community of color—to achieve national prominence. This sparked a burst in political and academic discourse surrounding institutionalized discrimination in environmental land usage policy that disproportionately impacted the poor. Instances of environmental injustices were increasingly documented and analyzed, and these studies were being published in prominent journals and news outlets. Eventually, case studies and official reports were being pushed by proponents of EJ to inform environmental and land usage policy decisions.

There were several milestones during the early years of the EJ movement that established its significance. In 1983, Congress’ General Accounting Office (GAO) released a report that provided the first region-wide statistical account of environmental injustice, confirming that three-fourths of the hazardous waste disposal sites in eight southeastern states are located in poor and African-American communities. In 1987 the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice published its first report, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, showing that the racial composition of a neighborhood is the single most important factor in determining where a toxic waste facility is sited. Sociologist and prominent EJ scholar Robert Bullard reinforced this contention in his review of EJ struggles in several black communities, in his book Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. These documents were instrumental towards the further advancement of the EJ movement, especially into the realm of federal policy.

The significance of EJ was further reinforced at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, where EJ leaders produced two landmark documents Principles of Environmental Justice and the Call to Action. Finally, EJ principles became written into federal policy when President Bill Clinton came to office and issued Executive Order 12898, which aimed to:

“focus Federal attention on the environmental and human health conditions in minority communities and low-income communities with the goal of achieving environmental justice. That order is also intended to promote nondiscrimination in Federal programs substantially affecting human health and the environment, and to provide minority communities and low-income communities access to public information on, and an opportunity for public participation in, matters relating to human health or the environment.” The stated purpose of the order was to have each federal agency, “make achievable environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations” (EPA definition of EJ, 1995).

The Bronx Joins the Environmental Justice Movement

NYC has a vibrant history of EJ activism that continues through today. The movement sprouted from the efforts of the West Harlem Environmental Action (WE ACT) organization that prompted activism in the city when they demanded improvements in the management of the North River Sewage Treatment Plant. Since the plant opened in 1986, residents complained of foul odors and respiratory problems. Over several years, the organization had dozens of meetings with city officials, assembled and presented data to support their position, and held public demonstrations of civil disobedience, but it ultimately took a lawsuit for the city to respond. Finally WE ACT reached a $1.1 million settlement in 1993 from the City of New York and received a promise of engineering improvements to decrease air pollution impacts of the Plant on the West Harlem community. Today, the facility continues to operate according to higher environmental standards, but of course problems remain.

The Browning-Ferris/Bronx Lebanon Hospital medical waste incinerator was built in the South Bronx in 1993, designed to process the medical waste of 12 NYC hospitals. Plans for an incinerator stirred controversy even before it was built, because the community knew that it would pollute the air and cause respiratory problems, but construction proceeded. The local community, activists, and environmental groups demanded it be shut down, especially after the data began to accumulate: asthma-related hospitalization rates doubled within the two years since the incinerator opened. Administrators from nearby schools claimed that the frequency of asthma-related sicknesses amongst their students doubled or tripled as well. The incinerator violated state pollution standards consistently throughout its operation, with minimal repercussions. They ended up accumulating over 500 citations, including excessive carbon monoxide emissions, which resulted in a paltry $50,000 fine and a mandate to provide $200,000 to fund Bronx community programs. Finally after years of resistance from the community and grassroots organizations led by the South Bronx Clean Air Coalition, the incinerator was “temporarily” closed in 1997 but eventually torn down to the relief of its opponents in 1999.

A more recent EJ victory in the Bronx was the closing of the New York Organic Fertilizer Company (NYOFCO) sludge fertilizer plant in Hunts Point in 2010, where more than half of NYC’s sewage was processed. Since the plant opened in 1992, nearby residents complained about the acrid stench hanging over the area 24/7, all year round. Some described the smell as that of “a filthy toilet” and “rotting meat.” The stench was so unbearable that people kept their windows shut and minimized their time outside, which prevented kids from playing outdoors and made outdoor recreation and festivities things of the past. Finally, after 18 years of complaints and protests, a lawsuit against the NYOFCO led by the community activist group Mothers on the Move in partnership with the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC), was settled in 2010.

Shutting down these private facilities wasn’t easy, as the respective campaigns required relentless persistence and resilience on the parts of the frustrated, but passionate community members. They faced inaction and pushback by city officials and corporate representatives often based on the argument that closing these facilities would result in the loss of “indispensable” waste processing capacity and loss of jobs; however, with these particular facilities the arguments fell short and could not justify the environmental nor human health costs of continuing business-as-usual. The medical waste incinerator proved to be unnecessary and provided few jobs. In the case of the NYOFCO plant, the City actually saved money by closing it and redirecting operations to alternative sites, including a landfill and a more cost-effective and sustainable facility located in rural Pennsylvania. And the loss of 40 jobs was compensated for by providing job placement assistance. Today Bronx residents continue to resist development of polluting facilities in the community, as South Bronx Unite is leading an ongoing legal battle against the opening of a controversial FreshDirect facility.

With the burgeoning green economy paradigm, it has been proven time and time again that economic development and environmental stewardship are not mutually exclusive as was once believed. In fact, Bronx-based innovative green jobs programs established in the early 2000’s have buttressed the workforce providing job training that addresses both unemployment and environmental sustainability at the same time. Communities shouldn’t be pressured to compromise their health and environment in the name of jobs or economic growth, and ultimately it should be the responsibility of the local and state governments to uphold these values through supporting beneficial programs, initiatives, and regulations.

Maladies in the Bronx: a closer look at the impacts of environmental hazards on health

Although the Bronx has taken long strides towards environmental restoration, the community is still riddled with a host of environment-based health problems, one of the most well-known being asthma. One of the most obvious concerns, specific to industrial site-laden communities, is the impact of air pollution on health, particularly respiratory health because it represents the first instance of contact between polluted air and the inside of the body. As asthma is a clear-cut consequence of respiratory health problems, it has been studied extensively as a consequence of poor air quality in the urban health field. Although asthma is a multi-factorial disease that is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, it has been well established that air pollution is a major exacerbating risk factor.

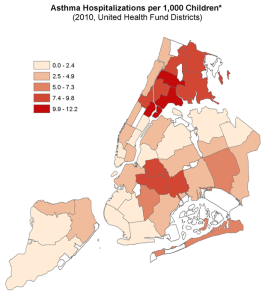

source: Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York (2013). Keeping Track of New York City’s Children, Tenth Edition. Figure 4.15

Asthma has been recognized as a grim and growing epidemic in the South Bronx for a long time, as asthma-related hospitalization and death rates have grossly and consistently outpaced the rest of the city, state, and country. Epidemiological studies showing clear links between air pollution and asthma (not to mention cancer, heart disease, metabolic diseases, and low birth weights) have been conducted in cities all around the country for decades. By the early 90s, health statistics made it obvious that the same phenomenon was happening in the Bronx, prompting community organizing, public health research, and a loud call for government action. According to the New York State Asthma Surveillance Summary Report, between 2009 and 2011 the Bronx had the highest age-adjusted asthma death rate in NYC at 43.5 per 1 million, more than twice that of the rest of the city and six times that of NY State. The problem is so serious that the NY Senate recently passed a bill that would direct the New York State Department of Health to study and devise a plan of action addressing the disturbingly high asthma rates. Among many other factors, the horrible air quality is recognized as a major factor affecting asthma incidence and outcomes. In a 2014 report, the American Lung Association gave the Bronx a dismal grade of “F” in annual air quality.

The South Bronx Environmental Justice Partnership (SBEJP) was formed in 2001 to address the growing health disparities plaguing the Bronx, specifically from the perspective of environmental justice. The partnership embodied the interdisciplinary approach necessary to understand and develop comprehensive solutions to the complex urban health issues unique to the Bronx population and environment. SBEJP is a consortium of academics, health professionals, community leaders, and government entities, representing diverse organizations, including biomedical research-based institutions Montefiore and Einstein, public universities Lehman College and CUNY, and a grassroots community organization For A Better Bronx, funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

One consequence that emerged from this partnership was a better understanding of the asthma epidemic in the Bronx. A SBEJP-supported study published in 2007 aimed to determine if there was a real connection between asthma hospitalization and proximity to sources of air pollution, including power plants, sludge processing plants, waste disposal facilities, and major truck routes that plague the Bronx. The study concluded that indeed, people living closest to these sources of air pollution were up to 66% more likely to be hospitalized for asthma (based on hospital data from 1995-1999), 30% more likely to be poor, and 13% more likely to be a minority than those outside defined buffer zones.

The South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study from NYU, commissioned by Congressman Jose E. Serrano and four grassroots Bronx community groups, further demonstrated the link between air pollution and asthma. Researchers monitored the air quality experienced by schoolchildren over a 3-year period, by having them carry around mobile air pollution monitors. They concluded: “Soot particles spewing from the exhaust of diesel trucks constitute a major contributor to the alarmingly high rates of asthma symptoms among school-aged children in the South Bronx” and that “If you live in the South Bronx, your child is twice as likely to attend a school near a highway as other children in the City.”

Beyond indisputably proving a real link between air pollution and asthma in the Bronx (which had already been well established in the literature based on studies of other low income communities), how have these studies informed and redirected existing urban planning, public health, and environmental policies? What real actions have come out of these studies? Well for one, the corporations profiting from the various polluting industrial facilities throughout the Bronx can no longer plausibly deny the possibility that their business operations could compromise the health of the community. And in direct response to asthma studies in NYC schoolchildren, anti-idling laws were strengthened. Furthermore, the pollution problem became a matter of fact and called the attention of academics, environmentalists, community activists, medical providers, policymakers and politicians, to advocate on behalf of the communities affected and promote further research into the issue. Additionally, environmental justice and its impact on the health of the Bronx moved to the forefront of many grassroots community organizations’ priorities, and even led to the formation of new organizations and community-academic-government partnerships to combat this major public health crisis. Grassroots and multidisciplinary efforts were instrumental to precipitating government action through the years.

Asthma represents just one example of the slew of health disparities that environmental justice communities, such as the Bronx, are disproportionately burdened by. More recent studies have also confirmed links between prenatal exposure to various urban air pollutants, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and fetal growth and neurobehavioral development. Results from the comprehensive Mothers and Newborns Study led by public health researchers at Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, examined a cohort of pregnant Black and Latino women from Northern Manhattan and the South Bronx and their children, and found that high prenatal exposures to PAHs were significantly associated with low birth weight and head circumference, delayed cognitive development, lower child IQ, ADHD, and even childhood obesity. These have further social implications with regards to educational performance and employment in adulthood.

The same noxious environmental toxicants (e.g. PAHs, ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, fine particulate matter, etc.) spewing from industrial facilities and vehicle exhausts are also the same toxicants that are linked to metabolic diseases, several cancers, and various adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In fact, in the spirit of the current anti-vaccination/autism pseudoscience spectacle, we should be worrying about industrial, traffic-related chemicals and pollutants contributing to autism, not vaccines. There is a growing body of evidence linking these chemicals to autism rates. Most recently, a Harvard study published this year, concluded confidently that air pollution is a risk factor for autism, particularly during the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. This area of research is still very much in its infancy, and “causation” is far from proven, but there are statistically significant correlations that are worth probing further. Although available data suggests that autism is NOT overrepresented in low-income communities (however it may be that autism diagnosis, not real autism incidence, occurs less in low-income communities), it may later emerge as an environmental justice issue. And in the larger scheme of things, we know that climate change will disproportionately affect the poor as well.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The link between hazardous environmental exposures and adverse health outcomes is undeniable. And we know that the poorest, marginalized communities (which also tend to be communities of color) are most vulnerable to these hazards, because of the noxious polluting facilities preferentially placed in their communities. Although EJ remains a pressing issue today, the EJ movement has successfully pushed these injustices into the national arena, forcing governments to respond. EJ is now integrated within Federal policy and has become a priority of leading institutions such as the EPA, NRDC, and various state, city (e.g. NYC Environmental Justice Alliance), and community-based advocacy groups.

What we learn from the EJ triumphs in the Bronx and elsewhere is that grassroots community leadership is requisite to reaching objectives, whether it be closing a polluting facility, or pushing a specific policy agenda through the legislative process. In each of these stories, it was the everyday people of the community that sounded the alarm, did the footwork, and screamed until the government responded—they rallied their neighbors, amassed resources from wherever they could, structured themselves into new community organizations, and strategically recruited and partnered with power brokers from academia, government, law, and the private sector to amplify their negotiating power and push their special interests. Despite constant setbacks, broken promises, and adversity, these grassroots efforts persevered and proved that enormous feats by seemingly powerless people are possible.

The flood of academic research linking urban environmental exposures to illness was instrumental to pushing EJ from being an issue of civil rights to an issue of public health as well, further legitimizing the complaints of the affected communities and the demands for policy change by EJ advocates. Public health scholars, scientists, and physicians continue to provide the data and medical authority needed to strengthen community-based EJ efforts. In the Bronx, Einstein and Montefiore have formed several partnerships with community organizations (e.g. BronxCREED, Bronx Health Link, etc.) to support community health programs, health disparities research, and policy change. Interdisciplinary approaches are necessary for comprehensively understanding community health disparities and environment and for identifying effective solutions.

Although there is still a lot of work to do, the Bronx has come a long way in realizing environmental restoration and better health. It has been difficult to precisely quantify how environmental improvements (e.g. shutting down industrial facilities, implementing more stringent air quality standards, providing green space, etc.) affect health outcomes, but nonetheless it is clear that the Bronx is an overall healthier and happier place to live.

In the backdrop of the fight for EJ, a “greening the ghetto” movement has been gaining traction as well, addressing the need to restore the beauty, health, and dignity of the Bronx and its people after decades of neglect, pollution, and degradation. The movement is based on the tried-and-true principle that open green space can transform communities into healthier, happier, and livelier places; green space encourages people to spend time outside, enjoy recreational activities, and interact with one another, promoting healthy lifestyles and cultivating a sense of community.

After rallying the community, securing government support, and implementing various programs, diverse members from the community were on the ground rebuilding the Bronx from the ground up—park by park, tree by tree, riverfront by riverfront. Although much work remains, the Bronx now boasts an elaborate network of parks, connected by greenways, bike paths, and pleasant walkways, proudly attracting visitors from the other boroughs. The Bronx has come a long way.

Any new industrial land uses proposed for development need to provide comprehensive, independently-evaluated studies about projected health impacts in the immediate environment, and concrete steps need to be taken to control the extent of those impacts. The host of existing laws and regulations must be vigorously enforced. Critics who complain about the excesses of the “big government” regulations and the threat to urban employment opportunities must be answered with hard data about the real consequences of these activities. The long-term costs of ignoring EJ issues, in terms of lost productivity and managing chronic health care conditions far outweigh any benefits.

Danielle is a Bronx transplant originally from Los Angeles. She graduated from UCLA with a B.S. in Biology and a minor in Anthropology. She is currently a senior-level PhD candidate at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, completing her thesis research on the function of hepatic nuclear receptor PXR and xenobiotic metabolism. In addition to her interests in basic science, Danielle has strong interests in science policy and communication, biotechnology, the environment, and social justice. She is Chief Editor of the EJBM Blog and a Writing Intern for the Department of Communications & Public Affairs at Einstein.